Introducing: Christian Theology and German Idealism

Why their Fundamental Solidarity is Important Today

I have been writing essays on Christian theology, German Idealism, and what I have been calling their fundamental or internal solidarity, their essential belonging with one another. In this essay, I want to take a step back and introduce the project anew, and clarify its motivations.

What fundamental solidarity means is that in order to entangle these two traditions, one ancient and one modern, it is not necessary to impose on either of them outlandish, unfounded, or heretical interpretations. All that matters is the form of thinking which they imply. To develop my fundamental solidarity claim we have been considering fundamental concepts in Idealism. This is not only to clarify the often misunderstood meaning and significance of Idealism, but also to show that its being a theological movement is not based first of all on any of its explicit dogmatic claims (e.g., any Idealist writings directly concerning the doctrine of God, Trinity, etc.). It is rather based on purely formal elements, fundamental, non-theological concepts in Idealism which I have been referring to as knots which entangle the two traditions.

An example will help illuminate the character of the proposed entanglement. When Christianity searched in antiquity for intellectual resources it could use to make itself intelligible to itself and others, i.e., when it sought to validate its own claims as true philosophy,1 it found the tradition of Platonism. Christians freely produced a relationship to Platonism which would become central to their identity. And they were not put off by the fact that, on the surface, Platonism is absolutely incompatible with the central Christian message of Incarnation. Rather than being led by surface-level dogmas, they, as Hegel would say, surrendered themselves to the concept,2 and were thus able to identify purely formal elements in the Platonic tradition—elements which would become ‘knots’ entangling Christianity and Platonism. These might include, for example, the pervasive theme of transformation in Plato’s thought, that the soul’s future is not discernible in the world of becoming, that it is capable of coming into its own as a new kind of being, another nature—this was fertile ground for theological reflection.

With a special combination of intellectual creativity and formal abstraction, early Christians were able to produce a relationship to a body outside themselves which became decisive for their future and identity. The early church was capable of this combination, of exposing her identity to outside influences, because of her confidence in the truth of her claims. What is true should be capable in this way of freely producing new relations to outside bodies, thereby becoming an image of not only the truth, but also the life. For this reason, the early church was not afraid of competing truth claims, and was able to engage her outsiders without the combativeness, insecurity, and resistance we see today but with confidence and grace.

The Church’s entanglement with Platonism was essential to the foundation of a gentile church. Pannenberg explains:

Such an appeal to the [Platonic] philosophical doctrine of God must not be interpreted only in an external sense as an accommodation to the spiritual climate of Hellenism. Instead it reflects the condition for the possibility that non-Jews, without becoming Jews, might come to believe in the God of Israel as the one God of all humanity. The appeal to the philosophers’ teaching concerning the one God was the condition for the emergence of a Gentile church at all. We must therefore conclude that the connection between Christian faith and Hellenistic thought in general—and the connection between the God of the Bible and the God of the philosophers in particular—does not represent a foreign infiltration into the original Christian message, but rather belongs to its very foundations.3

By forging a relationship to philosophical thought, early Christians were able to deliver on the gospel promise of universality; that the God of Israel is God of all people and nations, and that his promise given in Jesus applies to everyone. In short, the early church produced an intellectual relationship to a body outside it which made possible a new, real relationship to outside bodies, i.e., the masses of gentiles. In this way, it also did good on its promise that the church is a living being, free from the world’s idea of what an institution can be.

Part of what I want to show in this series of essays is that this example is of utmost importance for Christians today. Just like the early Christians who faced the challenge of communicating what they knew was a universal message to non-Jews, the church today is faced with masses of outsiders who take Christian truth-claims to be foreign, arbitrary, and dogmatic. Our outsiders oppose the freedom of thought to Christian doctrine, because from their point of view, Christian authorities exhibit none of the intellectual virtues enjoyed by early Christian Platonists, e.g., intellectual creativity, and the capacity to engage outsiders. It is time therefore to follow after the early church; to assume the risk of producing new relationships to outside bodies, to recouple Christian truth with abstract, philosophical thought, and to make universality once again into the guiding theme of the entire message. What I want to show, moreover, is that Idealism stands as the philosophical tradition ready to be received by Christian theology—specifically, Christian theology straining to make itself comprehensible and relevant to masses of secular, autonomous knowers; the masses of outsiders.

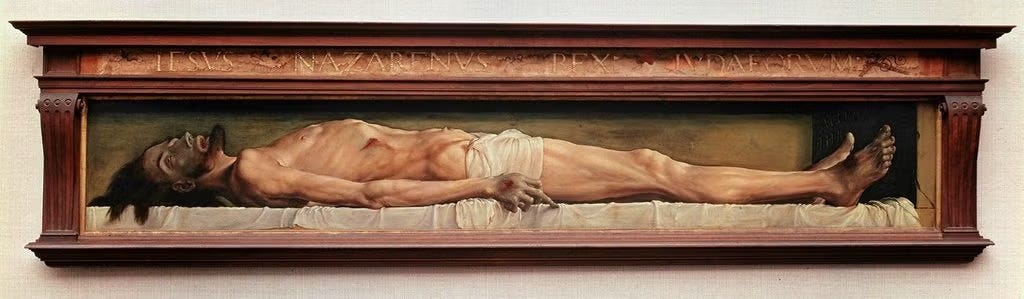

What motivates my arguments are these masses. Just like the early church, Christianity today faces the challenge of communicating itself to outsiders. The Hellenists who had to digest the outrageous idea that the god of Israel is their god too (and that he died on a cross), find their counterpart in today’s ‘cultured despisers’ who have to stomach the outrageous idea that obscure religious dogmas have something to do with free self-determination, and natural-scientific knowledge. The church has always had outsiders; and to the extent that the churches around me refuse to relate themselves to philosophical criticism and the natural sciences, I count myself one of them.

In my view, the way the church relates to its masses of outsiders decides its truth or untruth. If a church understands that what unites her members is what united Christ’s original followers, namely poverty, common lack, nonbelonging, exclusion from the world,4 then it will be free to produce new relations, to engage outside bodies, to enjoy the freedom of thought which is our greatest gift from God. But, on the other hand, if a church falls into the illusion that what unites her members is a robust identity, some possession held in common (e.g., nationality, success, feeling), it will relate to outsiders with the insecurity and combativeness we see today.5 That said, what will help the Christianity’s apologetic situation today will be, above all, dispossession and humility. It has to be freed of its pretensions, so that it can engage outsiders with grace, as opposed to insecurity and combativeness.

As an outsider myself, my aim with these essays is to allow the Idealist change to work itself on Christian theology so she can be dispossessed again and regain the plasticity she had when first found the Platonic idea of divinity; the wings which make us into other natures. The equivalent challenge today is to produce a new, entangled relation which binds German Idealism and Christian theology. Again, what effects the entanglement, as opposed to Idealism’s explicit Christian commitments (which in point of fact are not terribly reliable), is a set of pure forms, i.e., fundamental concepts in Idealism which I have been referring to as ‘knots’. We have thus far considered science and revolution in the first essay, and law and criticism in the second. Yet to be considered are the concepts of the subject and the absolute. But why Idealism?

These concepts not only form a foundation for Idealism. They mark the contours of the modern world, the same world we all live in, and the world where the Christian religion has no obvious place, where Christianity’s superfluousness or obsolescence continues to loom for some of us as a threat, for some as a promise. Science, revolution, law, criticism, subject, and absolute—the way things stand this is Christianity’s outside; each concept can establish a form of atheism. What I want to show by demonstrating the fundamental solidarity between Christianity and German Idealism is the truth of Hegel’s famous words: that Spirit wins its truth only when, utterly torn apart, it finds itself. For something that cannot endure self-division, its truth claims must be considered finite and relative. It is only the capacity to endure self-division which qualifies something as true.6 Therefore, if Christianity expresses absolute truth, it should be able to dwell and find itself within its own outside. The thought of the divine thus finding itself captures the Idealist adventure. Christianity’s pathway toward making itself the difinitive expression of truth in the modern world passes through Idealism.

E.g., https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/02101.htm

See Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit, s. 58, 70.

Wolfhart Pannenberg, Metaphysics and the Idea of God (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1990), 11.

Karl Barth, The Epistle to the Romans, Edwyn Hoskyns, trans. (London: Oxford University Press, 1965), 99f.

When I talk like this, I have in mind, for example, the masses of evidence accumulated by the YouTube Channel “Belief it or Not”. See

Paul Tillich makes this point in vol. 2 of his Systematic Theology. See Alexander J. McKelway, The Systematic Theology of Paul Tillich (New York: Dell Publishing, 1964), 85.