My friend just wrote about the conversion of St Paul, now here is a miniature version of the story, reverberating/repeating itself in my own life. (I believe it repeats itself in all our lives as a reminder that anything can happen. Impossibility is foundational for all of us, not just Paul.) I repeat Paul: I spent my undergraduate year a soldier against Platonism.

Another friend of mine recently confessed surprise at my ‘becoming a Platonist’. He rightly recalls that our shared anti-Platonism was “how we became friends”. So for these reflections, I want to ask what was the precise nature of my undergraduate ‘anti-Platonism’, and what was it, on a conceptual level, that, during my nine months in Cambridge, compelled me to renounce that descriptor. What happened to me?

I recall that in my first two (maybe three) years of undergraduate study, I was incapable of writing an essay without citing Alexandre Kojève’s Introduction to the Reading of Hegel. I started reading this very dangerous text in high school. I bought it at the Harvard University bookstore thinking it would be a run-of-the-mill helping hand for Hegel’s philosophy. (It was the farthest thing from that.) I had never heard of Kojève before. I was completely oblivious, and had no idea what I was getting myself into, how violently this Russian’s lectures would grip me, as it did Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, Althuser, Bataille and others. Someone should have warned me about that man!

Alexandre Kojève was a Russian born French philosopher who gave a seminar series on Hegel’s philosophy in Paris from 1933-39. As I suggested, several would-be famous philosophers and thinkers attended these seminars. The tradition we call ‘continental philosophy’ can take these seminars as a founding moment. But for Hegel scholars today, this is problematic because Kojève’s version of Hegel’s philosophy was far more original than he let on. What Kojève was doing was more forming his own philosophical enterprise (influenced by Heidegger and Marx) than presenting Hegel’s work. To produce what became a staggeringly powerful and compelling philosophical vision, he had to have his way with Hegel.1

One striking example concerns the ‘master-slave’ dialectic. If you have ever wondered why, in textbook-style summaries of Hegel, this short argument is made into the centre of his philosophy, Kojève is likely the reason. He made the ‘master-slave’ argument central to the exclusion of other (just as important) themes such as love and reconciliation. This was one of Kojève’s crimes, that he served up Hegel without love.

Another crime was that Kojève explicitly and without qualification, declared Hegel’s philosophy to be one thing, and Plato’s another. For Kojève, these were two mutually exclusive philosophical decisions concerning the absolute. And my undergraduate self thought that the Hegelian decision was better founded. This is how I became a soldier against Platonism.

Kojève writes: “the opposition between Plato and Hegel, then, is not an opposition within Philosophy. It is an opposition between Philosophy and Theology…”2 The reason the two philosophies are opposed is that one is philosophy and the other is theology. More precisely, the one (philosophy) affirms that the ‘Concept’, the absolute, is in time. The other (theology/Platonism), by contrast, affirms that the Concept can appear in time, but relegates its existence to the transcendent, outside of time.3

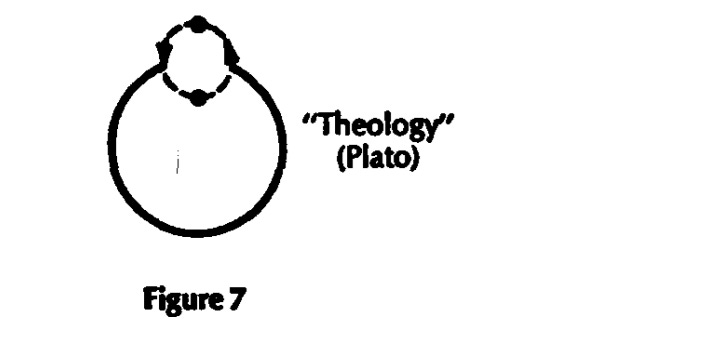

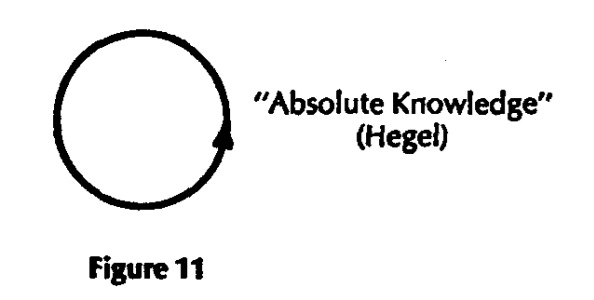

Put so abstractly, doesn’t the anti-Platonist option seem more parsimonious? If it's a matter of choosing between (a) the existence of two worlds and (b) the existence of one, a philosopher should choose one. Why should there be two? If there were, wouldn’t that cut against the basic impulse and meaning of philosophy, of Wissenschaft, which is to unify? Moreover, in this light, doesn’t Platonism feel like a copout? Wherever there is instability and contradiction, you can just say that that appearance is just an appearance or a shadow, and that being, in truth, has no blemishes. To hit his point home, Kojève even deployed a set of diagrams in which Plato’s theology is represented as a circle within a circle, while Hegel’s philosophy is a single circle, which is more elegent and parsimonious. Hegel was depicted as the philosopher capable of comprehending the world as a unity, having done away with the baroque and ideological pretensions of the old metaphysics.4

And now we have to recall that I was reading this while attending my Christian evangelical high school. Though an atheist, I was captivated by God-talk; debate about God, belief and reasoning. One thing which I found particularly insulting was the kind of God-talk which invoked divine unknowability at just the crucial moment. Everyone has heard ‘God works in mysterious ways’, or ‘who are we to pretend we have insight into his plan?’ This form of thinking, the cheap invocation of divine unknowability, has other, more sophisticated variants. What particularly stands out is the view that the Trinity, i.e., God’s very essence, has no relationship to the human intellect. How many Christians are today capable of holding a serious conversation about this most important Christian doctrine? Or what about Incarnation? Is your average Christian capable of saying anything meaningful when asked how it can be that Jesus is God but that his Father is also God? My high school experience did not seem to appreciate that internalizing and ultimately accepting Christian truth-claims requires thought. When faced with the demand for reasons, my teachers and peers would fall back on the doctrine of divine unknowability, a move which struck me as discrediting.

Pairing this frustration with Kojève’s atheism lead me to conclude that Platonism was the problem; so long as we affirmed transcendence, denied the knowability of the absolute, and were thus ready to accept truth-claims on external authority, then all kinds of domination is on the table, especially the emotional-manipulative kind which pervades American churches. Emancipation must therefore involve ditching the transcendent, ditching the other world.

Putting Kojève aside, Hegel’s own writings seem to support this program as well, in particular the ‘Force and Understanding’ section of The Phenomenology of Spirit. If anyone wanted to demonstrate that Hegel is a philosopher against Platonism, they would turn to this chapter. Nonetheless, I still take it to be one of, maybe the, most important section of the text. I will only give a desperately brief summary here.

In this section Hegel is dealing implicitly with Newtonian physics, the idea of force, and how it came about that all of nature was comprehended as law-governed. This discovery required a form of Platonism; all the change we experience, from the celestial to the terrestrial, is subject to basic stabilities (laws). But as the system of laws becomes more fleshed out, the relation between the world of change and the ‘stable kingdom of laws’ becomes confused. Are the concrete events expressions of the laws, or are the laws derived from concrete events? What causes what? Eventually, the result is a ‘two-world’ account with one world of appearances and another of transcendent constancy; a kind of Platonism. And this raises more questions. Does the stable world of laws appear at all? If not, what cognitive work can it possibly do? And if it does, in what sense is this appearance different from that which is appearing? In the end of Hegel’s argument, difficulties about the role of ‘appearance’ and ‘explanation’ in the ‘two-world’ account produce nonsenses, or, what Hegel calls ‘the inverted world.’

This is a notoriously difficult concept. It has none of the intuitiveness of the ‘master-servant’ argument, and has been thus unfortunately left out of most Hegel-summaries. I make sense of it as follows. The logic of the ‘inverted world’ is at play every time someone misunderstands the idea of transcendence as a kind of change-machine. For example, when it is said that because God is so transcendent, his love does not appear as love but as wrath or test, this is the inverted world. His beauty is our ugliness. Or when it is said that God reveals himself by concealing himself, we may be dealing with the inverted world. The transcendent is where everything is opposite to how it appears. In this world, everything that is last is, in the other world, first. Although Hegel speaks jokingly saying ‘sweet is sour, sour sweet, up is down and down is up’, the position he mocks lives on today.5

The reason I summarize Hegel’s inverted world argument is to show that, by opposing Hegel and Plato, Kojève was not just making things up; Hegel does pose formidable and complex challenges to Platonic ideas. Hegel follows Kant in the ‘Consciousness’ section of the Phenomenology by attempting to show that a ‘two-world’ metaphysics inevitably fails the demands of philosophical science, i.e., it produces nonsenses and arbitrariness, or in Kant’s words, ‘dialectical illusions’. I was certain that the nonsenses and arbitrariness issuing from many Christian mouths were due to the fact that they had surrendered divine knowability, invested in crude transcendence, and were caught in the inverted world.

But does Platonism really boil down to a ‘two-world’ metaphysics? Does his theory of self-subsisting transcendent ideas really capture what his philosophy is all about? If it did, Kojève would have been right to declare Plato’s philosophy one thing, and Hegel’s another altogether. It was in Cambridge that I began to see that Plato has more to offer, and that there is more continuity stretching from him to Hegel than some French marxists would lead you to believe! Kojève’s claim about the direct opposition between Hegel and Plato is unfounded.

To see why this is the case, one need only follow Hegel’s own argument from the ‘inverted world’ and to Self-Consciousness. For another inadequate summary: Hegel sees a close connection between the structure of self consciousness on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the nonsensical and arbitrary work of the understanding as it tries to hold its ‘two-world’ model together. The understanding wants the two worlds to be unified (that way one can express the other which expression in turn explains it), but also distinct. It engages in what Hegel calls explanation, a circle one sees often in scientific discourse; ‘why did this event happen in that way?’ ‘Because of the law which determined it so.’ ‘Why is that law the way it is?’ ‘Because that is how those events happen.’ This going around and around, or what Hegel calls ‘the production of differences which immediately cancel themselves as differences,’ is how the structure of self-consciousness gets inadvertently imaged within ‘Force and Understanding.’ It is self-consciousness which differentiates itself from itself, only to cancel that difference into a basic unity, the ‘I’. When the understanding wants to talk about the transcendent realm of laws, it is in fact talking about itself, its own structure. When it splits the world into pure idea and concrete event, what is really at stake is its own power to split apart and bring together (itself).

Know thyself: during my nine months in Cambridge, Douglas Hedley slowly taught me that this injunction deserves to be at the centre of Platonic philosophy, and not the forms as they are commonly understood. This was crucial in part because, this way, Platonic philosophy is bound inextricably to modern philosophy beginning with Descartes, a tradition which also turns around the investigation of the self. Hedley’s work, then, can be seen as a re-suturing of Platonism to modern philosophy and contemporary concerns, in the wake of Kojève’s violent act of severing the two.

But what is the meaning of the oracle’s injunction? When one ventures to know first of all themselves, one finds a being or a life which is unlike anything else one will ever encounter. It is free, self-moving, productive, it can differentiate itself from itself while remaining single; it is infinite. It cannot be reduced to external causes, mechanisms, or anything finite. Changing Platonism’s centre of gravity from the doctrine of forms to the infinite soul enlivened his philosophy for me. Opposed to the forms as they are normally conceived, the self is mobile, vital, always different. It is plastic.

The Phaedrus conveys this very strongly, equating the soul with the capacity for self-movement, assigning to the human soul the capacity to detach itself entirely from the world of experience,6 and also to conceive and issue from itself ‘living words’ which can impress the souls of others.7 But the plasticity of the soul is also treated in Republic VI. As Socrates explains what virtues the philosopher should nurture, one gets the sense that what is at stake is a new nature. Poet, king, slave, soldier, and now, philosopher; in this section of the Republic, Plato introduces the world to a new shape the soul can take.8 The freedom which the soul is capable of for Plato rivals Sartre's notion of freedom in its radicality.

The soul often seems like a conservative and backward idea, much like ‘essence’. It seems to imply a binding identity, an inflexible stability, when in fact the opposite is the case. Take this quote from Catherine Malabou. When being interviewed the question of ‘essentialism’ came up;

First of all, if you allow me to say a few words about essence and essentialism, … it is very vital for me to- precisely this is related to my being a philosopher … that an essence is, contrarily to what people say (something fixed and solid)- an essence is a transformative entity. And what philosophers have called ‘essence’ is not a substance, it is a principle of transformation.9

For Malabou, an essence does not fetter; it animates, mobilizes. It is able to facilitate something’s becoming other. An idea of transcendence thus enters the horizon which has nothing to do with a ‘two-world’ account, but rather with the incredible plasticity of being. The constant theme of transformation and transfiguration in Plato’s philosophy should be surprising to no one: against our modern assumptions, when beings are tethered to essences, they cease to be predictable. I think C. S. Lewis had a similar idea when he wrote in Till We Have Faces:

I dreamed, again and again, that I was in some well-known place-most often the Pillar Room—and everything I saw was different from what I touched. I would lay my hand on the table and feel warm hair instead of smooth wood, and the corner of the table would shoot out a hot, wet tongue and lick me. And I knew, by the mere taste of them that all those dreams came from that moment when I believed I was looking at Psyche's palace and did not see it. For the horror was the same; a sickening discord, a rasping together of two worlds, like the two bits of a broken bone.

Awkwardly for me, he literally says ‘two worlds’ in the passage. However, what distinguishes Lewis from Hegel’s representation of ‘two worlds’ philosophy is that for Lewis, the two do not fit together. In Hegel’s case, a second world is invoked to explain the first, render it predictable, and the two are meant to fit seamlessly together. With Platonism it is different. Unlike consciousness in Hegel’s ‘Force and Understanding’, what Plato demands is self-investigation. The reason for this must be because in the self produces its own foundation; in the self risides the vitality, instability, the self-relatedness, which belongs to all being: everything is divine. Put this way, Plato is the philosopher for the project unfolding on this page: to demonstrate that theology, as a problematic, is not an artificial addition to, but belongs at the foundation of modern philosophy. I leave you with Hadot:

If the Forms require no explanation, and contain within themselves their own justification, the reason is that they are living beings: "That which is inert and lifeless has no raison d'etre at all; but if it is a Form and belongs to the Spirit, whence could it derive its raison d'etre [sc. except from itself]? (VI, 7, 2, 19-21).

The world of Forms is animated by a single Life: a constant movement which engenders the different Forms. It is like a single organism, which finds its raison d'etre within itself, and differentiates itself into living parts.10

See for example

Alexandre Kojève, Introduction to the Reading of Hegel, Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit, James H. Nichols, Jr., trans. (London: Cornell University Press, 1980), 89.

Ibid, 106ff.

Ibid, 105.

G. W. F. Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit, A. V. Miller, trans. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977), 157f.

Plato, Phaedrus, Robin Waterfield, trans. (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2002), 245e.

Ibid, 276a.

Plato, Republic, G. M. A. Grube, trans. (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1992), 484b.

Agon Hamsa and Frank Ruda, Crisis and Critique, “Catherine Malabou on the Clitoris, AI, Anarchism, Hegel, Marx, … and much More!”

Pierre Hadot, Plotinus, or the Simplicity of Vision, Michael Chase, trans. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 39.

https://maypoleofwisdom.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/plotinus-or-simplicity-of-vision.pdf